They report for duty in uniform — khaki shirt, name tag over the left breast shirt pocket, and a cap with an embroidered emblem that looks like lightning bolts. A patch on the left sleeve identifies who they are: National Park Service Volunteer. They’re surrounded by electronic relics— most still working— that take up space and make a lot of noise.

Before the Internet, email, and satellite communications changed our lives, there was the telegraph—the lifeline of dots-and-dashes called Morse code, transmitted over the airwaves so ships at sea could talk to land-based radio stations. There were hundreds around the world and dozens in North America. Most have disappeared, with only one still on-the-air in North America— KPH radio station, San Francisco. The NPS volunteers are keepers of the faith, inside an art deco style building at the end of a long road canopied by Calfornia cypress trees on Point Reyes National Seashore.

In the heydey of the telegraph, mighty RCA (Radio Corporation of America) owned KPH. Before moving to Point Reyes, KPH first operated from San Francisco’s Palace Hotel in 1905. A year later the Great San Francisco Earthquake struck and forced the station to relocate. It was regarded as the “wireless giant of the Pacific.” The station received incoming telegraph messages from its transmitter in nearby Bolinas, California, including the infamous message of December 7, 1941— the Japanese invasion of Pearl Harbor. At the time, Morse code was the only way ships could send distress signals. It was the standard ship to shore communication for 100 years, eventually replaced by advances in electronic communications technology near the end of the 20th century.

The last Morse code ship messages to and from KPH ended on June 30, 1997. The National Park Service then stepped in and took over the KPH property. The building was shuttered for two years before Richard Dillman, president of the Maritime Radio Historical Society—a small volunteer group of self-described “radio squirrels”— convinced the National Park Service to let them bring KPH back to life. The non-profit group pays for the operation through small grants, donations, fundraisers, and money out of their own pockets. Dillman says he and others in the group find creative ways to fix and maintain some of the electronic relics. After all, spare parts are hard to find. A storage room inside KPH is a trip back in time as shelves are stacked with vintage radio receivers. Before the coronavirus pandemic, visitors to Point Reyes National Seashore could visit the KPH building every Saturday for tours, and observe volunteer radio operators communicate via telegraph over open maritime channels to the few ships around the world still equipped to send and receive telegrams. Now the KPH radio building is closed and will remain that way until California moves to phase 3 COVID-19 reopening. The state is currently in phase 1. Still, the closure has not deterred the KPH volunteers, according to Roy Henrichs, who heads operations and maintenance for the Maritime Radio Historical Society. “We are working to resume transmitting Morse broadcasts on maritime frequencies from an alternate transmit site in Valley Springs, CA, ” explained Henrichs via email. “That is experimental development work, but initial testing began last Saturday (September 5, 2020). That should keep us on the air through the end of the COVID event, as well as any future event that takes us off the air at Point Reyes.”

A dedicated bunch of radio squirrels doing whatever it takes to stay on-the-air and preserve history.

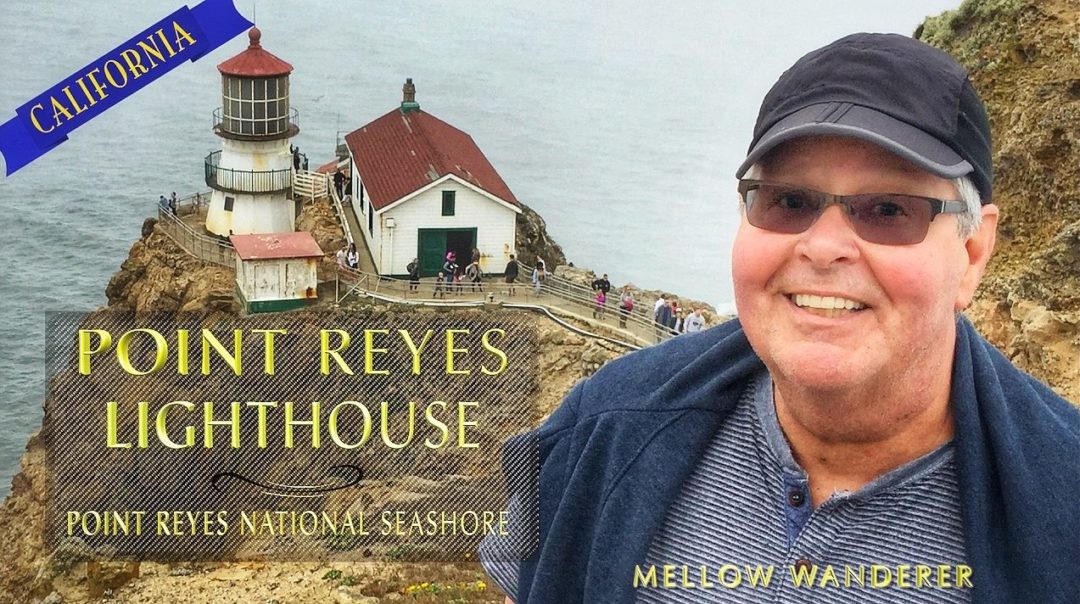

KPH PHOTO GALLERY